Introduction

On Tuesday, November 5th, I sat with my entire blocking group in our Eliot House dorm, huddled around a small TV, each anxiously nibbling on the picnic of snacks we had bought in preparation. With four of us being Government concentrators, Election Night was an exciting, but also nerve-wrecking moment. While we all recalled Election Nights since 2012, this one held particular significance, since it was the first time we were able to cast our own ballot. On top of that, no election before had felt as critical as the one in front of our eyes that night. Bouncing between MSNBC’s Steve Kornacki and Fox New’s Bill Hemmer, we watched the election map coverage from 7PM to 1AM. Supplemented by The New York Time’s election coverage and X doom scrolling, the night took us by complete surprise. After months and months of campaign analysis and predictive polling, Donald J. Trump has been elected the 47th President of the United States of America.

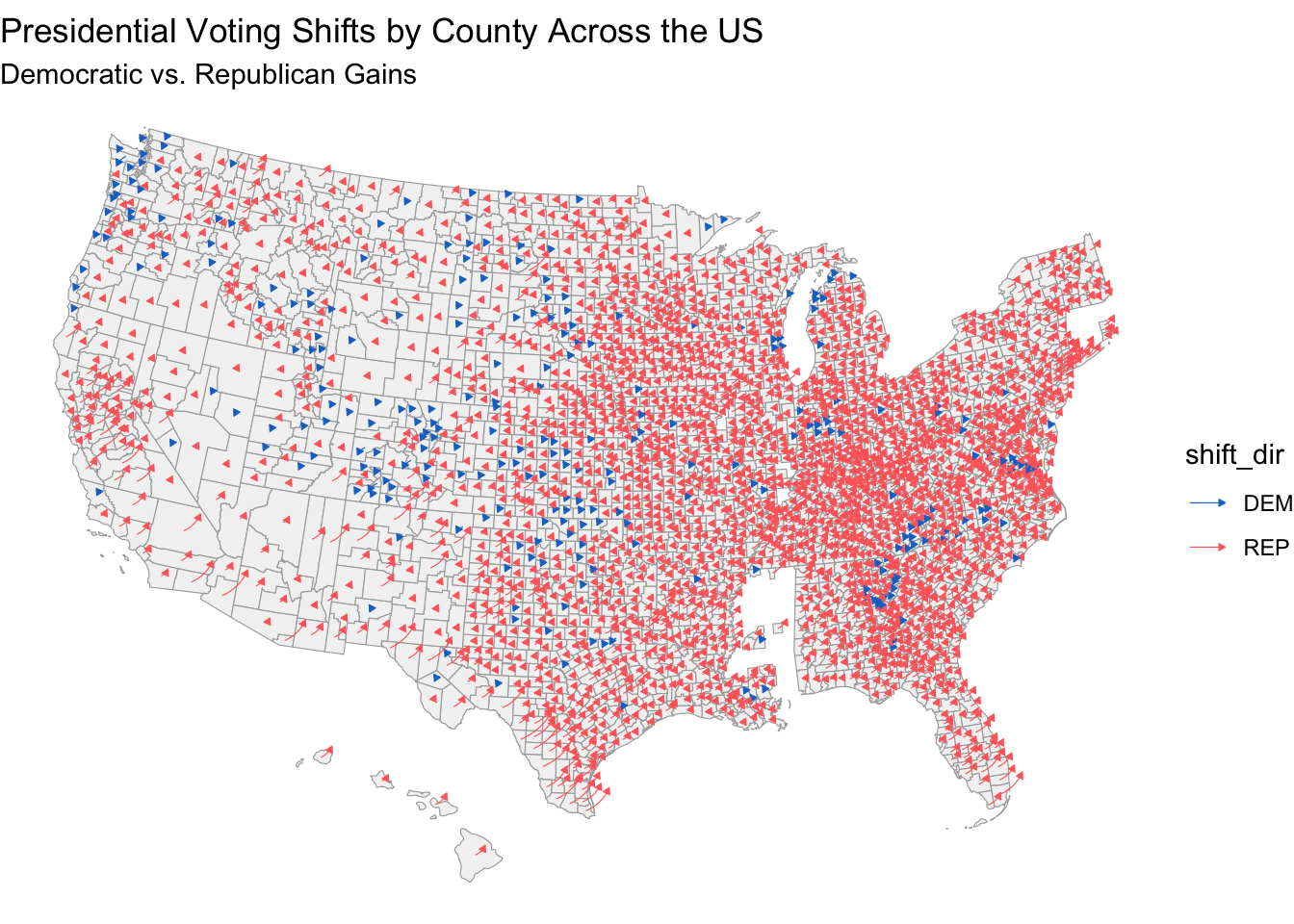

To be clear, the winner was not what surprised me and my roommates. But instead, the magnitude of his victory was astonishing. Across numerous sites, analysts disagreed on who would win this election, but almost all agreed that it would be close. Yet, Trump declared victory in every single swing state, and saw voting shifts in a large majority of counties, relative to 2020. He made great progress among Black and Latino voters, as well as middle-class families. In this blog, I will analyze the election results relative to my own prediction model. I hypothesize that the results fit into an international pattern of backlash against incumbent parties, driven by inflation and post-pandemic economic challenges, leading to most U.S. voter groups swinging toward Republicans. However, key exceptions, such as swing states and urban areas, suggest nuanced shifts, including decreased racial polarization and growing class influence in politics.

Reviewing My Model

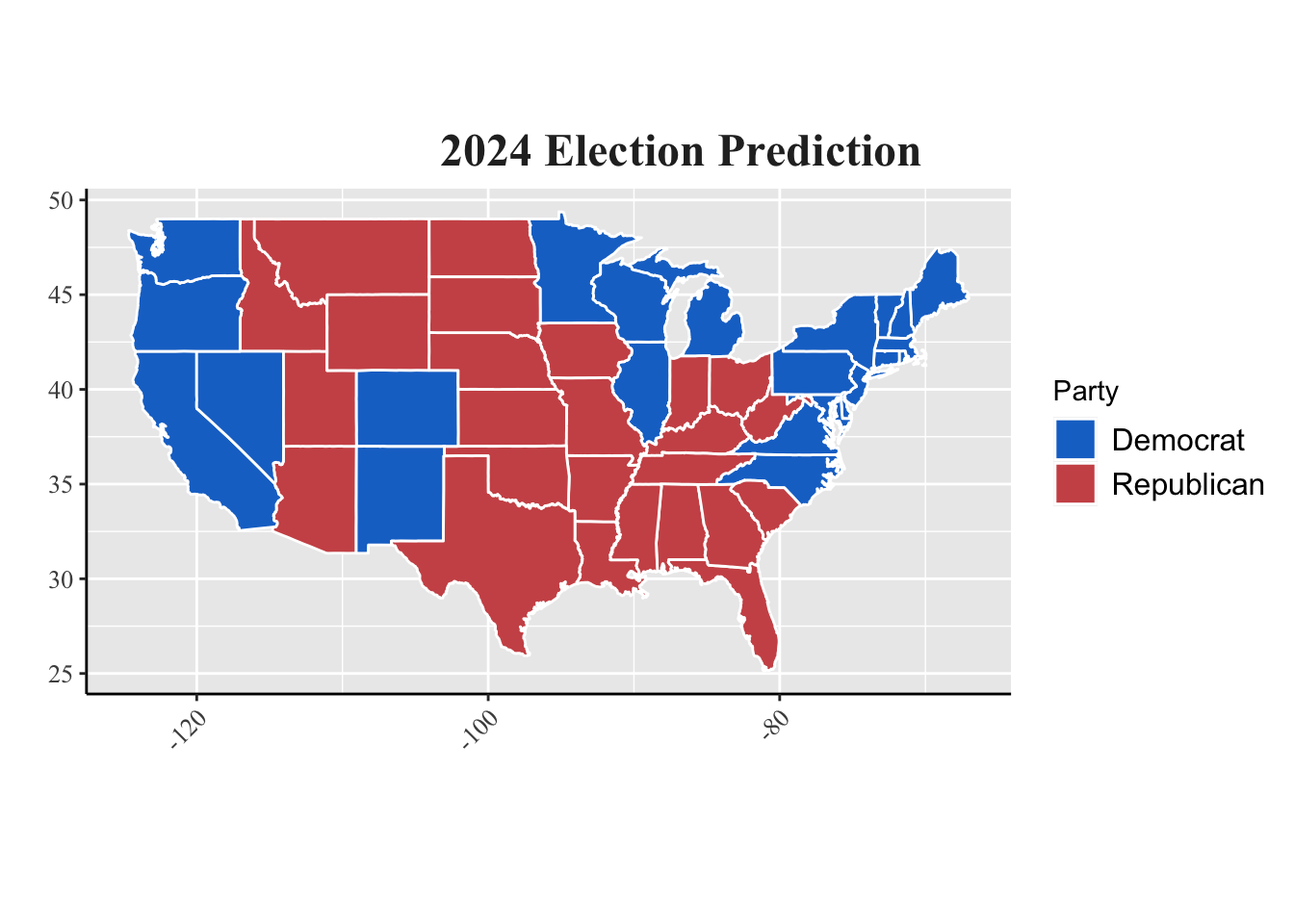

To recap, my model predicted the outcome of the seven swing states established: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. The remaining states were assumed to align with the 2020 election outcome. My model contained the following variables: democratic two-party lagged vote share, latest and mean polling averages, second quarter GDP, unemployment, and incumbency. I used a LASSO regression and also accounted for weighted error. As you can see below, my model predicted that Kamala Harris would win all swing states besides Arizona and Georgia.

However, because my margin of victory was minimal with a popular vote share between 49 and 51 percent, I included a 95% confidence interval. In these results, the lower interval gave Trump the popular vote win in every swing state besides Nevada, while the upper interval gave Harris the popular vote win in every swing state.

How Accurate Was I? (Hint: Not Very)

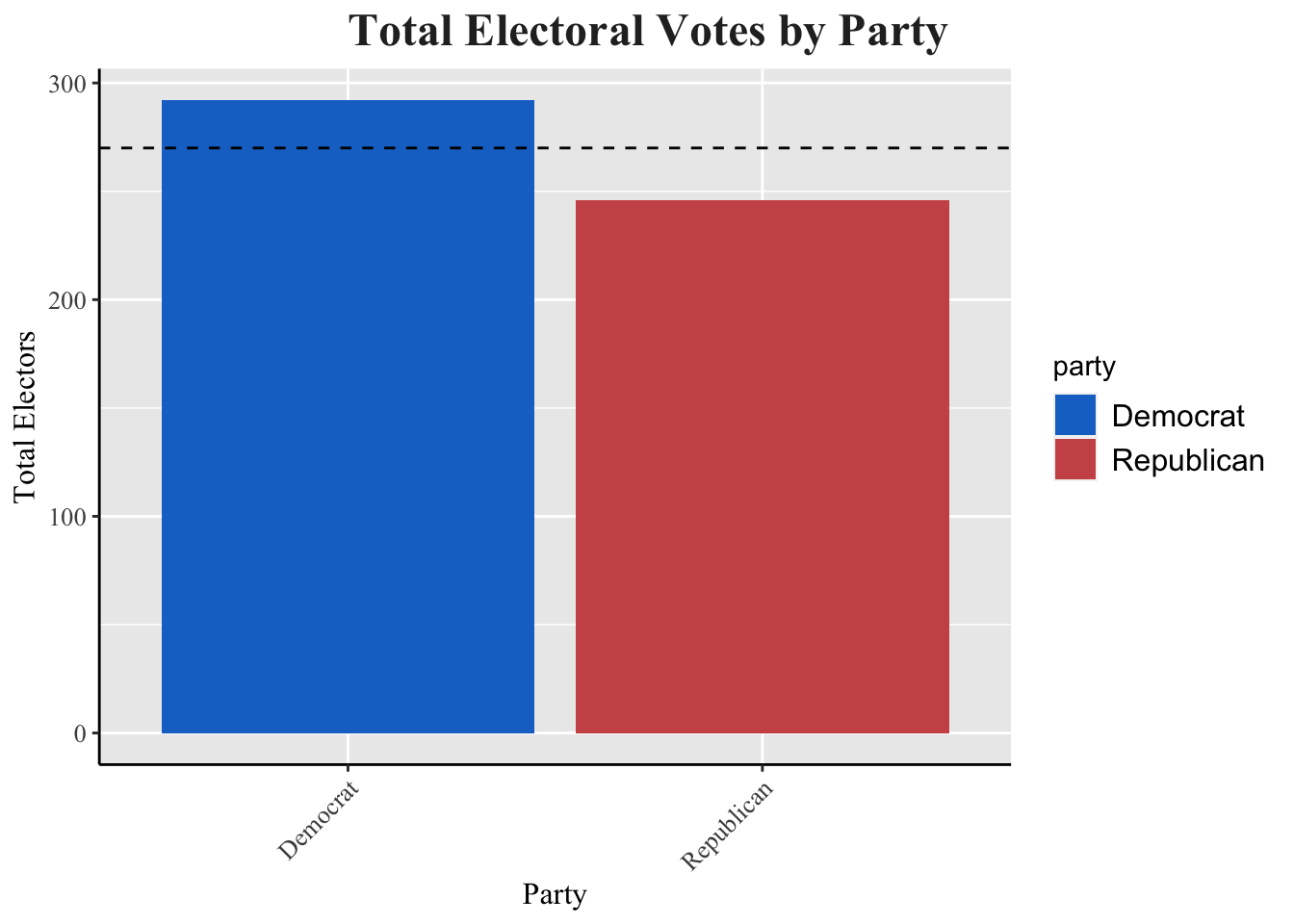

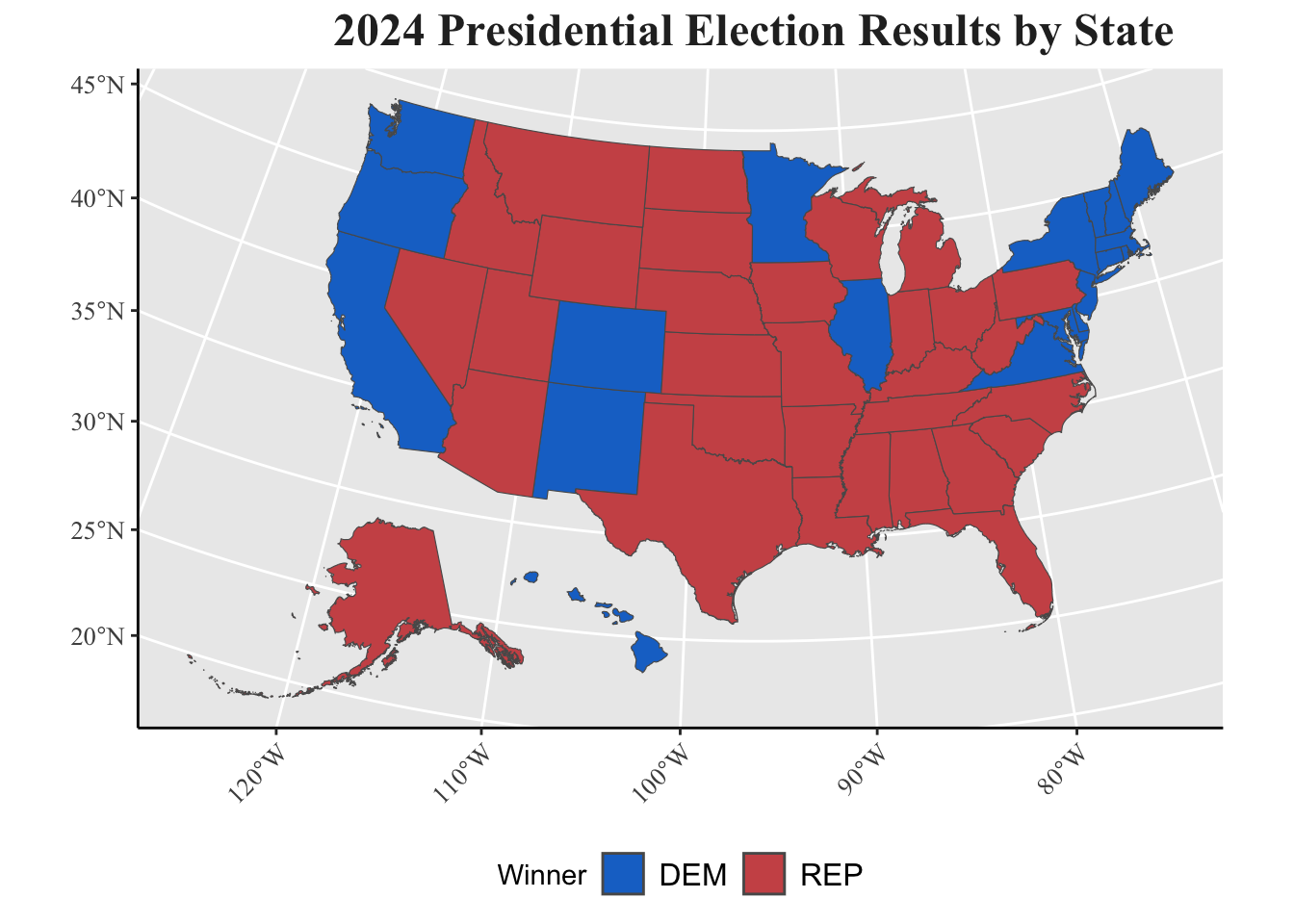

The final results of the election gave Trump 312 electoral votes and Harris 226 electoral votes. Trump also won the popular vote with 50.1 percent of the vote share. Ultimately, Trump was victorious in all seven of the established swing states, giving him a margin of victory that left many pollsters in shock.

While I correctly assumed that every state besides the swing states would match 2020 results, my model incorrectly predicted that Trump would manage to swing all 7 swing states red. Further, my model overestimated Harris’ popular vote share in every state, which can be seen in the error column. The state I had the best prediction for was Georgia, which makes sense because Georgia has one of the greatest number of polls, so its accuracy has been better since 2016. Essentially, most pollsters were most accurate in Georgia, and since my model was heavily reliant on polls, it fits that Georgia performed the best in mine too. Interestingly, Arizona was the only other state I accurately predicted, yet it had my second highest margin of error—after Nevada. Additionally, a small win in my model was that, between Week 8 and 9, I accurately updated my prediction for Georgia and Nevada. I do think it’s useful to note, also, that my lower 95% confidence interval would’ve been much more accurate, likely because of the tight race that polls were predicting. Later in this blog, I will dive further into hypotheses of why my model failed.

Table: Table 1: Comparing 2024 Democratic Vote Share Prediction and Outcome

| state | Predicted_Harris_2pv | Predicted_Winner | Actual_Harris_2pv | Actual_Winner | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 49.82948 | Republican | 47.15253 | Republican | 2.6769535 |

| Georgia | 49.74125 | Republican | 48.87845 | Republican | 0.8628003 |

| Michigan | 51.33334 | Democrat | 49.30156 | Republican | 2.0317848 |

| Nevada | 51.73468 | Democrat | 48.37829 | Republican | 3.3563924 |

| North Carolina | 50.14996 | Democrat | 48.29889 | Republican | 1.8510655 |

| Pennsylvania | 51.14048 | Democrat | 48.98235 | Republican | 2.1581335 |

| Wisconsin | 51.35674 | Democrat | 49.53156 | Republican | 1.8251821 |

The evaluation metrics for my 2024 election model provide some important insights into its performance in predicting the Democratic vote share. The bias of -2.11 indicates that, on average, my model overestimates the Democratic vote share by approximately 2.11 percentage points, suggesting it tends to predict higher vote totals for Democrats than actually occurred. The Mean Squared Error (MSE) of 4.96 reflects that my model’s predictions deviate significantly from the actual results. The Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) of 2.11 reveals that on average, my predictions are off by 2.11 percentage points.

Table: Table 2: 2024 Prediction Evaluation Metrics

| Metric | Error |

|---|---|

| Bias | -2.108902 |

| Mean Squared Error | 4.959900 |

| Root Mean Squared Error | 2.108902 |

Why Was My Model Inaccurate?

Across the country, Trump made impressive progress in gaining more voters than he was able to in 2020. Once again, the polls were were unable to predict this progress, either overestimating Harris or underestimating Trump. This year, Trump built support with white women, Black men, Latino voters, young voters, and suburban voters. The map below shows these voting shifts across counties overwhelming in favor of Trump, relative to his vote share in 2020.

Now, I will list a few reasons why my model failed in predicting the presidential outcome.

Polling Data: As mentioned throughout this blog, my model included latest polling averages and mean polling averages as two of the six variables used. However, as seen in 2016 and 2020, polls have been unsuccessful in predicting Trump support, often underestimating his vote share. For example, the three polls I followed most closely were the New York Times, FiveThirtyEight, and RealClearPolitics—all of which predicted a Harris win. Since the polling data I used for my model came from FiveThirtyEight, there was an overestimation in her success that my model did not control for. In the Trump era of politics, polls have shifted in his direction much more in the week leading up to the election. This year, among voters who made their decision in the final week of the campaign, 54% chose Trump, while 42% selected Harris. Among those who decided in the last few days, 47% supported Trump and 41% backed Harris. I hypothesize that my model, thus, would’ve been more effective using only the last week’s polling data, though still, I will now further discuss why polling data is tricky with Trump as a candidate.

Candidate-Specific Effect: To begin, Trump has transformed political preference distinctions. His dramatic character and controversial language has made his support across different demographics hard to predict. For example, a week before election day, people may have assumed that women would protest his anti-abortion stances, Latino voters would protest his rhetoric around immigration, and Muslim voters would protest his Islamophobic legislation. Yet, none of this was seen to be true. Similarly, polls have been unable to crack the secrecy in voter surveys. People have continued to falsify their preferences, presumably as a result of Trump’s controversial takes, making surveys unrepresentative of election day outcomes. There is also definitely an candidate-specific effect that hurt Harris, but was hard to quantify in my model, and many others. For one, it’s hard to ignore the fact that Harris is a Black and Indian woman running for the highest office in the United States. Voters hold prejudice in their assumption of what a strong commander-in-chief looks like, and oftentimes, it is not a woman. Further, Harris was heavily burdened by a shortened campaign that only lasted 15 weeks. While the beginning of her campaign was filled with energy (and donations), she was ultimately cursed by President Biden’s legacy. People’s ultimate distrust for the Democratic party, and specifically the economy, in combination with a shortened campaign, left Harris unable to build her own individual platform, outside of Biden. In order to combat the Harris Effect, I would have included Biden’s June approval rating and created a variable to address implicit bias towards the race and gender of candidates, which I will workshop in the next section.

Economic Circumstances: Inflation proved to be a much bigger factor in this election than GDP, due to international context. The Financial Times reported a fascinating finding that “Every governing party facing election in a developed country this year lost vote share, the first time this has ever happened.” I’m glad I added unemployment as an economic indicator, but I should’ve also included inflation, on top of Biden’s june approval rating.

Personal Bias: Finally, upon reflection, I’ve come to understand how much personal bias plays into manipulation of election models. I, personally, tweaked my model based on what I saw to be likely versus unlikely, and I was ultimately hurt by this. Specifically, before finalizing my Week 8 and 9 models, I had numerous outcomes, two of which showcased a complete Republican sweep and a complete Democratic sweep. Having bias from my knowledge on other polling sites, I was misinformed in believing that this election would be close, so I didn’t believe that a sweep was a likely outcome. Now, I know that I was misled in this belief. There is not much I can do now to account for this, but it is a finding I came away with, and found valuable in thinking about in the future.

Testing My Hypotheses

To summarize, I would have made the following changes to my model: Trump-Specific Effect, Harris-Specific Effect, inflation variable, Biden’s June approval rating, less emphasis on polling.

Trump-Specific Effect: Luckily, this is Trump’s third time running for President, so there were two other examples of how polling predictions versus actual outcome played out. I would’ve looked at how 2016 and 2020 data varied between prediction and outcome, and applied that inaccuracy to my model to ensure that Trump was not being underestimated.

Harris-Specific Effect: This effect is slightly harder to quantify, because Hillary Clinton is the only comparable candidate to test misogyny, but she is a white woman so the racial implications don’t apply. For this reason, I would apply a small weight on polling data that focused on favorability questions, such as “Who is a stronger leader?”, “Who is more charismatic?”, etc.. I believe that implicit biases could be showcased in this personality questions.

Inflation variable: Quite simply, I would apply the 2023-2024 inflation variable onto Harris’ vote share model, as it would showcase the frustrations that voters across the world put on incumbent parties during elections.

Biden’s June approval rating: I would apply Biden’s June approval rating, since I hypothesized that Harris was hurt by the incumbent’s last few months of campaigning.

Less emphasis on polling: I would just include the last week of polling data, and apply a smaller weight to it.

Looking Back

Overall, I’ve had an extremely enjoyable time following this election, and have learned so much as a data scientist, historian, and government analyst. As I’ve already discussed my quantitative lessons from this semester, I will also discuss some qualitative ones. One, elections are hard to predict due to the limited number of elections that have been happened. It’s difficult to use data from 1948 to model a 2024 election, but due to the constraints, we often have to. I wonder what would’ve changed if I spent more time looking into elections from 2000 and on, as opposed to elections starting almost a century ago. I also would have liked to spend more time researching the polls that I used in my model. While I’m sure that FiveThirtyEight experts did better than I could’ve, I would’ve liked to see if there would be an improvement from hand-selecting a few polls based on my own evaluation. Additionally, as much as I have hypothesized improvements in this blog, I stand by my approach that simplicity is key to an election prediction. At the end of the day, fundamental economic variables seem to be the best predictor, so I am happy with my use of those.

Sources

https://abcnews.go.com/538/states-accurate-polls/story?id=115108709

https://www.ft.com/content/e8ac09ea-c300-4249-af7d-109003afb893

https://hls.harvard.edu/today/election-law-experts-provide-post-election-insights-and-analysis/

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-polls-underestimated-trumps-support-again/

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/07/us/politics/biden-harris-campaign.html